Our latest news and views English

Underpinned by our Scandinavian design heritage, we bring you regular stories about architecture and interiors, exploring natural materials, acoustics, and the creation of safe and harmonious environments.

As more and more employees are returning to the office, there is much talk about the role of the physical office space; whether it might be obsolete and how a hybrid setup is going to work in practical terms. Social aspects to office life such as communication and collaboration are cited as benefits of returning to a central office space. But with this renewed socialisation can come greater exposure to noise compared with homeworking. And while there are health and safety guidelines regarding very loud noises, when it comes to the everyday workplace distractions like other people’s phone calls, there’s less legal protection.

Although these types of noise aren’t as harmful to our ears as, say, a pneumatic drill, they nonetheless can cause stress and make it difficult to concentrate, especially if people are exposed to them for a longer period of time. A report entitled ‘The Cacophony’ by the Swedish National Association of the Hearing Impaired suggests that this type of noise can lead to symptoms such as tiredness, headaches and memory issues, as well as a sense of alienation.

Many aspects of modern workplace design make matters worse; hard surfaces such as exposed brick and large windows can actually add to the problem. Furthermore, The Cacophony report suggests that acoustics aren’t always fully considered by designers and their workplace clients. But as mental wellbeing in particular is at the top of many architects’ agendas, addressing acoustics in offices should be a primary concern.

Workplace acoustics depend on a number of factors: the sounds being made, the interior layout, background noise e.g. from ventilation systems, and other external sounds. However, one of the most important aspects is the sound absorbing qualities of the space. Linked to that is the concept of reverberation.

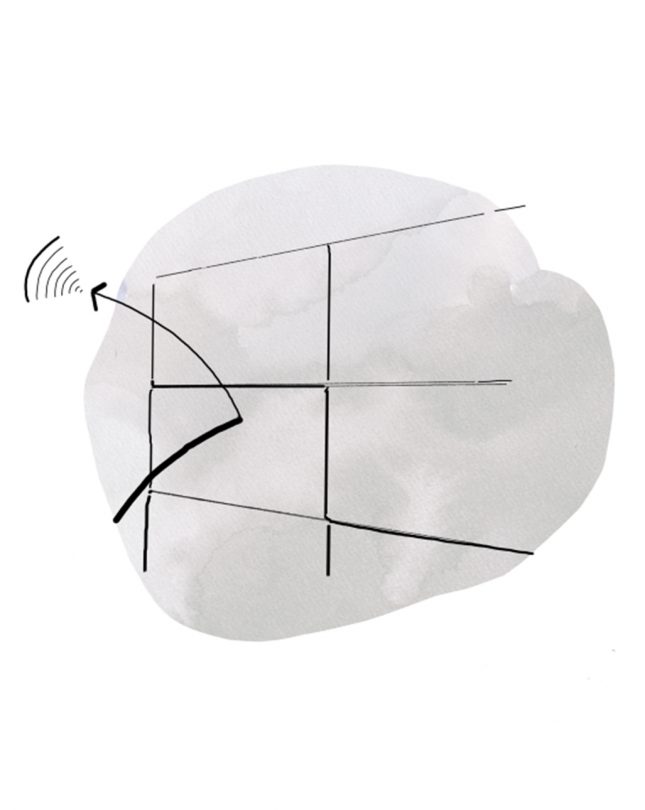

When someone talks, or a phone rings, the sound will propagate in all directions within a space. In other environments such as lecture halls, this distribution of the sound is an important aspect of the function of the room (so all students can hear the lecturer). In office environments by contrast, you don’t want noise propagating across the entire floor, but staying local instead, so colleagues aren’t disturbed.

The good news is that architects can improve the sound absorbing qualities of an office, by prioritising the acoustic properties of the materials they specify. Here we introduce five points for architects to understand when designing a workspace for both collaborative and concentrated work.

The reverberation time is the time it takes for a sound to become inaudible in a room. Harder surfaces and large open spaces allow sound to ‘reflect’ and bounce around the room, creating long reverberation times. Longer reverberation times mean more disturbance, as there is a build-up of sound and this can lead to a snowball effect, where people raise their voices further and thus add to the problem. The best formula for shortening reverberation times is to consider the three aspects of volume and shape of the room, shielding of sound, and absorption.

It’s important to understand that all materials in a room play an important part in its acoustics. More specifically it is the sound absorption properties of the materials that matter; whether they dampen or reflect the sounds, i.e. whether they reduce or prolong reverberation times.

With the addition of absorbing finishes on walls and ceilings, as well as floors, the acoustic characteristics and also the volume and shape of a room can be completely altered. It’s therefore important for architects to not just view materials in terms of their aesthetic properties but also what role they can play in absorbing sound.

When it comes to calculating the total sound absorption in a room, the materials’ absorption properties work together with the total surface area. Large existing surfaces such as walls and ceilings are often the best place to start when aiming to increase sound absorption and reduce sound reflections.

This is backed up by a 2018 paper ‘Acoustic Issues in Open Plan Offices: A Typological Analysis’ in the academic journal ‘Buildings’. The authors point out that it’s recommendable to “act first on the false ceiling and on the taller part of the walls, then with fixed or mobile systems to divide the space…”.

The measure of how well a material can absorb and convert an impacting sound, relative to one square meter of material, is known as the sound absorption coefficient. A sound absorption coefficient of 1 means a material absorbs the sound completely, while a completely sound reflecting surface would have a coefficient of 0.

A highly absorbing material spread over a small area will be just as effective as a large area with a low coefficient. And again, the more absorption, the shorter the reverberation time, which is the desired effect in an office environment! To understand more about the sound absorption coefficient, and how the different frequencies of sound play in, visit our acoustic academy section here.

The Cacophony report highlights the problem of bringing in an acoustics expert when it’s too late and the client or architect wonders why the space looks so good when it sounds so bad. Instead, we recommend bringing on a qualified acoustician as soon as practically possible within a project.

Although the open plan office has encouraged communication and teamwork, it is often to the detriment of quieter work, as the prevalence of rows of desks and multiple collaboration zones make it harder to concentrate. By understanding how your material choices can influence the acoustic experience, and making sure expert support is brought in from the start of the project, architects can create harmonious workspaces that safeguard the wellbeing of workers.